Destination Stewardship Report – Spring 2022 (Volume 2, Issue 4)

This post is from the Destination Stewardship Report (Spring 2022, Volume 2, Issue 4), an e-quarterly publication that provides practical information and insights useful to anyone whose work or interests involve improving destination stewardship in a post-pandemic world.

Beneath the waves at Ataúro Island. Photos courtesy ATKOMA.

Ataúro Island Revives a Conservation Tradition

Another winner from the Top 100 – Green Destinations organizes the annual Top 100 Destination Sustainability Stories competition, which invites submissions from around the world – a vetted collection of stories spotlighting local and regional destinations that are making progress toward sustainable management of tourism and its impacts. From the winners announced last year, we’ve selected this one from Timor-Leste, which showcases how restoring and expanding an indigenous tradition is helping one island restore its unique reefs, supported by responsible tourism. Submitted by Mario Gomes, President. Asosiasaun Turizmu Koleku Mahanak Ataúro (ATKOMA), the DMO for Ataúro Island. Synopsis by Jacqueline Elizabeth Harper.

In Timor-Leste, Little Ataúro Island Makes Big Waves in Marine Conservation

At 25 square kilometres in area, what Ataúro Island lacks in size it makes up for in abundance of biodiversity. This micro island belonging to Timor-Leste lies in the Indonesian archipelago just north of the country’s capital, Dili, on the eastern portion of the island of Timor.

Ataúru Island, due north of Dili, capital of Timor-Leste. Credit: Google Maps.

Ataúro is home to one of the most biodiverse reefs in the world and has the highest average of reef fish species on the planet. Controlling exploitation of these natural resources has been difficult. The majority of Ataúro inhabitants come from a long history of fishing livelihoods, but due to a limited number of police and forest guards, overfishing went largely unregulated. Cases of blast fishing have damaged several coral reefs around the island.

Nevertheless, the abundant aquatic life has recently turned this island into a popular diving spot. Timor-Leste has had an 82 percent increase in international tourist arrivals since 2011. Yet tourism here is still in its relative infancy. The marine habitats have huge potential for responsible nature and adventure tourism, which can add economic value and offer economic diversification to the island. Ataúro Island is now focusing on nature protection and biodiversity conservation to foster growth in low-impact sustainable tourism.

A Traditional Code Revived

Visit to an Ataúro reef.

To protect natural assets and endangered areas, Ataúro has reemployed the traditional Timorese practice of tara bandu in recent years, pushing it into formal law. Tara bandu is being used as a code of behaviour and community ritual that uses local conservation knowledge and expands community cooperation. While the literal meaning of tara bandu is “prohibition by hanging,” today this traditional code for natural resources management is applied to any activity or behavior that may damage forests or marine resources and negatively impact the community. If a person is found guilty of violating tara bandu restrictions, they are not hanged, but fined money or by handing over assets to the community. Violators usually comply; to do otherwise would be essentially sacrilegious in local tradition.

Adoption of tara bandu has successfully established 13 Marine Managed Areas (MMAs) across the island. The community of Adara, located on the Western side of Ataúro, was the first to use tara bandu in 2016 with the purpose of creating a “no take” MMA to protect the reef habitat, to promote sustainable fisheries and food security, and to encourage marine ecotourism. Its success led to 12 more MMAs being established around the coastline between 2017 and 2018.

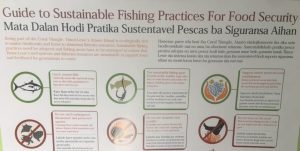

According to the Sustainable Management Plan for Ataúro Island, each of the MMA sites includes a core area that is ‘no take’ and it is surrounded by a buffer area. Activities permitted in these areas are governed by Suco regulation (pdf, p80), a written document explaining the rules pertaining to the area’s land and sea resources, ensuring future generations can access them (see poster below). In the no-take areas, all fishing and gleaning activities are forbidden, except in a few scenarios. In the buffer areas fishing is permitted only by using semi-traditional fishing techniques and during agreed-upon times. The regulations are the same for each site.

Tourism’s Contribution

To offset the loss of fishing income, there is now a $2 tourism fee paid to the local village council for every guest who swims, dives, or snorkels within the MMA. In 2018, the village of Beloi earned over $10,000 from this income stream. However, tourist visitation is not distributed equally across the island, so there are steps afoot to create a collective management system.

As Timor-Leste has only recently become independent, tara bandu is a way for locals to reclaim ownership of their natural resources and revive local traditions suppressed under the years of Indonesian occupation. Community support is important. Tara bandu will not work without complete support and buy-in from the local community. Through tara bandu and monitoring of the MMAs, biodiversity has improved in the no-take zones. Dr. Sylvia Earle, a famed ocean explorer, has recognized the people of Timor-Leste for their extraordinary commitment to ocean conservation.

Find the complete Good Practice Story from Ataúro Island, Timor-Leste here (pdf).

About DSR Contributors

Volunteer contributors are welcome to the Destination Stewardship Report. Contact us with your proposals and ideas.