Destination Stewardship Report – Summer 2022 (Volume 3, Issue 1)

This post is from the Destination Stewardship Report (Summer 2022, Volume 3, Issue 1), an e-quarterly publication that provides practical information and insights useful to anyone whose work or interests involve improving destination stewardship in a post-pandemic world.

Aerial image of Pulau Goal, Mersing, one of Malaysia’s nearly 848 islands. [Photo courtesy of Mohd Farithrizal Bin Md Zain, Jurufotografi B19, MBIP]

A Malaysian District Collaborates Lest Tourism Run Wild

Why would a place with relatively manageable tourism create a sustainable travel destination coordination group? While many destinations around the world are reeling from the impacts of over-tourism, including environmental degradation, a few are heeding the warning and proactively putting a plan in place. One such is the Mersing District in the Malaysian state of Johor, just north of Singapore. Cher Chua-Lassalvy discusses what it took to rally the district’s numerous, varied stakeholders and create the collectively managed Sustainable Travel Mersing Destination Coordination Group.

Mersing? Where’s that?

I have a friend who goes by the name Mersing Guy on Facebook. He was born and bred in Mersing and runs the local recycling business in town. Mersing Guy (true to his name) loves showing his visiting friends the hidden gems in his beautiful home district. A few weeks ago, we stood in front of the gold-domed Masjid Jamek looking out across the charming coastal town and beyond to the coral-ringed islands that dot the emerald sea. Mersing Guy always says that he is truly lucky to call this place home. It is a sentiment I have heard echoed many times from locals and it is easy to understand why.

The stunning hilltop mosque, Masjid Jamek Bandar Mersing, illuminated at night. [Photo courtesy of Chan Hyunh Photography]

Mersing District is located along the east coast of peninsular Malaysia’s southernmost state of Johor. It is the third largest district in Johor and encompasses a land area of 2,838 square km (including the offshore islands). Mersing is most famous for its eco-diverse islands described in the Lonely Planet as:

“a constellation of some of Malaysia’s most beautiful islands. Of the cluster of 64 islands, most people only know of Pulau Tioman, the largest, which is actually a part of Pahang. This leaves the rest of the archipelago as far less-visited dots of tranquillity.” The Lonely Planet

Besides the islands, Mersing is host to other natural wonders including long stretches of untouched mainland coastal beaches, mangrove-lined rivers, and pristine and little-visited rainforest reserves. Endau-Rompin National Park in the north of the District is the second largest national park in Peninsular Malaysia, encompassing 870 square km and protecting the only remnant of native lowland tropical rain forest in southern peninsular Malaysia and mainland Asia.

Given its rich nature and biodiversity, Mersing attracts both domestic and international tourists. However, according to the Mersing District Council, Mersing remains comparatively undiscovered, with the District receiving approximately 250,000 tourists per year pre-Covid, a little lower than the 270,000 tourists registered annually at the better-known, single island of Pulau Tioman in nearby Pahang.

Why Does Mersing Need a Destination Coordination Group?

As Mersing sees relatively little tourism, one questions the need for the district to have a destination coordination group to focus on sustainable travel. Many local stakeholders including government, businesses, and residents nevertheless recognise that without guardianship and management, our fragile ecosystems risk being damaged. Many of us have seen how mass-tourism and over-tourism destroyed natural wonders in destinations close to us. We did not want this to happen on our own turf and wanted to put measures in place to manage tourism sustainably.

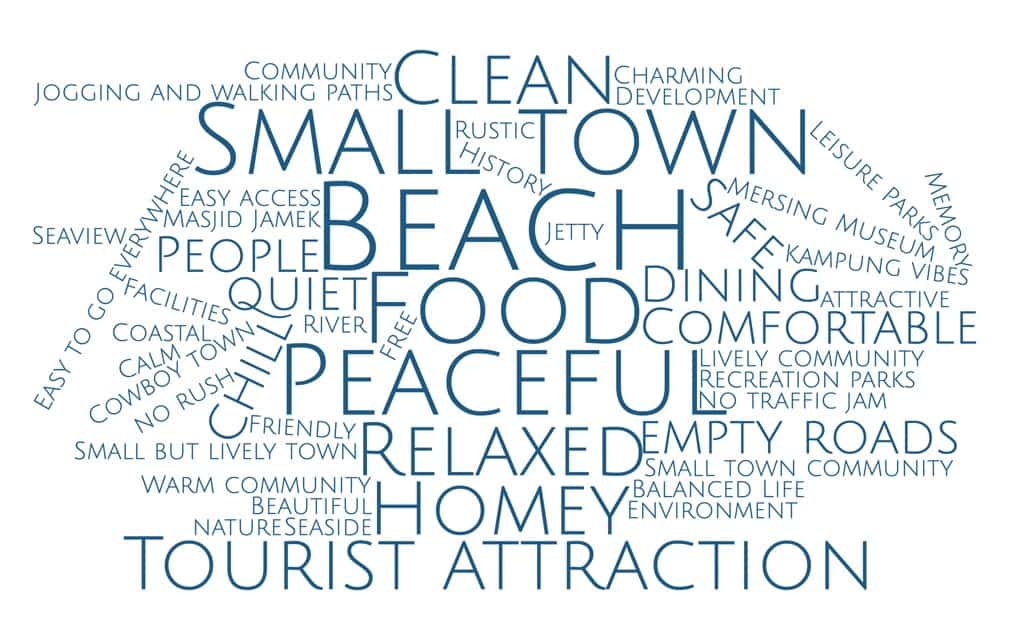

Word map based on the question asked via an online survey of Mersing’s community “What is your favourite thing about Mersing?” An exercise undertaken as part of Cultural and Bio-Asset Mapping of Mersing 2020. [Image courtesy of Majlis Daerah Mersing, Think City Malaysia and KakakTua Guesthouse & Community Space]

How Sustainable Travel Mersing Came About

Launch of Cultural and Bio-Asset Mapping of Mersing 2020 Project by Majlis Daerah Mersing, Think City Malaysia and KakakTua Guesthouse & Community Space. [Photo courtesy of KakakTua Guesthouse]

As a local stakeholder group composed of government, NGOs, private sector, and community leaders, our working group developed and took the proposal to set up a Mersing DCG to multiple meetings across government agencies at Federal, State, and District levels as well as to receive the blessing of the Johor Palace, which houses the royal Sultan of Johor.

In mid-2019, after six months of presentations, awareness-raising and persuasion, Sustainable Travel Mersing STM DCG was founded. Its aim is to support the development and growth of tourism that allows communities and businesses to thrive alongside healthy ecosystems. As a stakeholder group, STM uses the Global Sustainable Tourism Council Destination Criteria to guide its work. The goal for the destination is to become certified as a sustainable destination by 2025.

The Work

STMDCG has since created work plans based on priorities guided by the four pillars of GSTC’s Destination Criteria. The on-ground work has included:

- Development of a DCG and Secretariat with Terms of Reference in place

- Scheduled monthly meetings to brainstorm strategy, work plans, apply for funding, and present work completed

- Holding town halls and focus group discussions for local stakeholders and collecting input, thoughts and opinions on sustainable tourism in Mersing

- Collating feedback and relevant available information, then using these to create priorities for STM

- Co-writing the first iteration of a sustainable tourism strategy largely based on the GSTC’s Destination Criteria. The strategy is currently out for consultation.

- Collectively applying for funding on a collaborative basis to meet the aims of STM.

In addition, individual government departments, NGOs and private sector participants also continuously push forward with individual projects around marine and terrestrial conservation, stakeholder engagement, up-skilling, capacity building, creating guidelines, and mapping, which collectively add to the goals of STM.

Whilst Covid has delayed outputs and progress of STM, the activities and advocacy so far have resulted in some subtle changes. For instance, the Malaysian government increasingly cites and labels Mersing district as an eco- / nature tourism hub within Malaysia. This has resulted in steps by various players, including a pilot project by Majlis Daerah Mersing in partnership with a local university for an online tourism registration, monitoring, and governance portal. Though still in its early stages, it highlights the government’s will and interest in managing tourism and its impacts.

There has also been increased interest in Mersing from external agencies and funders in supporting post-Covid economic recovery, in particular the development of resilient, sustainable, and community-led tourism in the District.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

STM’s progress was greatly hampered during the two years of Malaysian Covid lockdown. In addition to being unable to meet physically as a working committee, we were also set back because we could not conduct training and stakeholder consultations in a community uncomfortable with digital interfacing.

Besides the Covid years, the work across multiple stakeholders and varied geographical landscapes has posed various challenges. However, these challenges have provided us with some important learnings outlined below.

- Ground-up initiatives can get off the ground if there is enough patience, perseverance and will.

- Every location needs a different approach to sustainable tourism, but we can learn deeply from other destinations journeying on the same path.

- We currently run STMDCG without a full-time project management team. All participants give their time voluntarily. To forge ahead in the journey towards certification, we feel that we need a funded full-time project team to truly propel the project forward. We feel that this needs to be led by a project manager with one or two junior officers.

- Human connections are key. It is a top priority to have STM’s aims more widely disseminated to tourism operators, resort operators, owners, and other community stakeholders. We believe this is best done through a mix of more formal town halls and focus groups as well as small group informal meetings and coffee or “makan” (eating in Malay) sessions.

- A diverse stakeholder engagement team is essential, as different ethnic or gender groups in communities feel more comfortable speaking to different members of the group.

Co-creation with multiple stakeholders can be a lengthy process requiring a lot of patience, however this leads to joint ownership of the project’s directions and is a worthwhile exercise. - The diverse mix of landscapes (islands, rainforest, mainland coast) creates challenges, and we are still grappling with how to best tackle them. For now, we include trips to remote small islands and indigenous communities (which can be costly) as well as mainland stakeholders.

- Creating a recognised DCG working on sustainable tourism has amplified interest in Mersing as a sustainable tourism destination. This has brought increased funding and projects focused on biodiversity conservation and responsible tourism into the area.

Today as I finish off this article, we have come out of our first physical post-Covid STMDCG meeting here in Mersing. How wonderful to finally sit around a table, eat local snacks, connect on a human level, and physically put our heads together again. I look forward to post-Covid reopening with optimism and hope the work we are planning will make Mersing Guy proud.

About the Author

Cher Chua-Lassalvy is Co-founder and Managing Director of Batu Batu – Pulau Tengah, a sustainably-minded off-grid island retreat in Malaysia with a focus on generating profits through tourism to create positive impacts in the local area. She is also the President and Founder of Tengah Island Conservation, a Malaysian non-profit biodiversity management NGO working within the Johor Marine Park. Batu Batu and TIC together were the proud winners of the World Travel Market Responsible Tourism Silver Award for Best in Conservation & Wildlife (2019).